The Historic Cotton Mill VillagePortrait of a Community |

Introduction

History of Chicken Hill

Mill Village Life

Workplace Hazards

Children & Mill Village Schools

The Company Store & Welfare Work

Introduction

In the 1880s the South emerged from the smoking wreckage of the Civil War with hopes for prosperity tied to the whirring of spindles and beating of looms. It was the textiles mills that built the New South. Agriculture dominated the southern economy until the mid 20th century; but by the 1920s, as railroads crisscrossed South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia, a new society rapidly took shape. Families who had once tilled the soil rushed to the mills to earn an hourly cash wage. This region quickly surpassed New England as the world’s leading producer of yarn and cloth, resulting in two decades of rebellion and modernization that culminated in the General Textile Strike of 1934. In the aftermath of this conflict, manufacturers began to abandon the mill village system, unmaking this distinctive form of working-class community.

|

|

|

|

|

By 1900, 92 percent of southern mill workers lived in villages owned by their employers. Within these villages, the millhands created a new way of life; the mill village was not only a place to live and work, but became the setting in which men and women fell in love, married, reared children and retired. Through learning the history of the mill village society, we have a unique opportunity to witness the stories of men and women whose roots lay in an agrarian past and whose lives and identities were transformed by factory labor.

The information provided here is common to most of the mill villages of the southeast. All the pictures presented in this gallery are from Chicken Hill and were generously shared by Clark Holllins of Hearns Cycle and Fitness, Max Price, Jimmy Smith, and others.

back to

top

Photograph of mill worker children on Chicken Hill circa 1950. Inscription on back says, "Daisy Jo's mad because

Jim got to wear Freds cap and she didn't." Courtesy of Jimmy Smith (left.) The old Clubhouse is the far left building.

History of Chicken Hill

History of Chicken Hill

Chicken Hill, situated just west of modern day downtown Asheville, North Carolina, was originally built as a mill village for the C. E. Graham Manufacturing Company. Located above the banks of the French Broad River, the mill was built during the Reconstruction Period of the 1880s by a group of local businessmen. These men considered it a regional imperative to rebuild the South in a way that could compete economically with the progressive industrialism of the North. This not only meant building factories, but meant retraining the working rural poor into this new industrial society. Cotton mills were a natural step toward the independence of southern cotton growers who were previously dependent on northern buyers for their raw product. The construction of the railroad along the French Broad River and into Asheville in the mid 1880's created huge business potential. Graham quickly capitalized on the opportunity and soon had the cotton mill up and running.

While most southern cotton mills were close to the growers, Asheville had the advantage of being closer to the coalmines whose fuel ran the machines of the factory. Coal was used not only to drive the machinery at the cotton mill, but as a fuel to heat and cook as well. Coal was a cheap and efficient resource, but proved to be a very dirty one. By the time a writer working for the WPA project came through Asheville in the 1930's, the area was coated in dark gray soot from the coal that was burned in the river basin. It is not a stretch to assume that the wealthy residents who lived at the top of Chicken Hill had moved there to escape the pollution! Today the factory is gone and coal has been replaced with natural gas and electricity, but in many older homes in Asheville you can find remnants of an open coal-burning fireplace or furnace in the basement (see 58 Park Square.)

While the mill was under local ownership, the workers were housed in Stick Style Victorian homes with a communal bathhouse and clubhouse. Several homes on Chicken Hill survive from this period such as the Clubhouse and the Ida Crowley house (Hanger Hall). These homes, which were built by the local mill owners, are quite large and display a fascinating level of detail and variety. The Clubhouse, for example, with its saw tooth gingerbread and stick style band boards, was built to express a certain level of optimism and playfulness not normally associated with cotton mills.

This optimism seemed to trickle down from the upper echelon to the workers who invested their free time and money into building churches for the area. Often mill owners would contribute money and land for the creation of churches for the workers. This would give them some pull with the preachers who enodrsed the godly virtues of hard work.

By 1894 the mill was purchased by Moses and Caesar Cone who were on their way to becoming major players in the textile industry of the south over the next decade. The Cone brothers began a major expansion: they enlarged the mill and covered the hill with houses for the larger work force. The homes were mostly identical one-bedroom cottages that lacked the architectural details of the earlier homes. Along with the smaller homes were built some larger two and three bedroom homes. These structures had more architectural interest both inside and out and housed people of authority such as the superintendent and floor foremen. Often these homes were placed in strategic locations so that they could monitor the comings and goings of the workers.

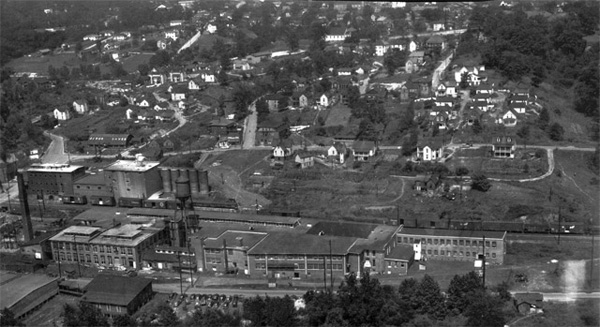

The Asheville Cotton Mill, as it became known, would continue to expand over the following decades, with at least one major additional expansion during the 1920's. Like most of industrialized America, the village suffered layoffs and economic hard times during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Following the second World War, after years of limited investment, the mill owners began divesting themselves of their holdings on Chicken Hill. Starting in 1949, with the struggle to compete with overseas markets, the mill began selling houses to the factory workers, taking out a small sum from their paychecks. This continued until 1953 when Caesar Cone finally shut down the mill, leaving the new homeowners unemployed. The building stood vacant for many years until 1995 when it was deliberately burned down leaving only one small portion.

From the closing of the mill until around 2000 the neighborhood suffered decline. What was once a vibrant community, with neighborhood stores and people connected by common working experience, became plagued with unemployment and outward migration as people abandoned their homes to move to better jobs elsewhere. Many of the structures did not survive abandonment; some fell down, some burned down, and some were even burnt intentionally for Fire Department practice burns. Out of the approximately 100 homes and apartments seen in the 1912 bird’s eye view drawing, only 33 exist today.

All was not completely bleak for Chicken Hill during recent decades, however. In 1973 Howard Hanger purchased the Ida Crowley Estate (see Hanger Hall ) and began a major restoration project on the most lavish surviving home on Chicken Hill, which now also houses Hanger Hall School for Girls. This was followed in the 1990's by a small trickle of people moving into the neighborhood and a large revival of the warehouse area on the river as artists have moved in to take advantage of the industrial spaces. See River Arts District for more information about the warehouse studios.

This development has in turn lead to increased investment in Chicken Hill. A great example is the award-winning restoration of the Parsonage, which was undertaken by the owners of Highwater Clays and Odyssey Galleries as a guesthouse for visiting artists. Whit Rylee, who specializes in historic preservation, restored the Parsonage for the current owners. He went on to revitalize 1 Park Ave. North and is now developing the Chicken Hill Co-Operative and other sites in the community. With downtown booming and RiverLink working to revitalize the French Broad River, Chicken Hill is experiencing a major surge in interest as a convenient and interesting place to live.

back to

top

Mill Village Life

A typical mill village consisted of the superintendent’s residence, single family dwellings, one or more churches, a humble schoolhouse, and a company store. When farm families moved to the mill village they brought with them their familiar customs which included bringing along the hogs, chickens, and cows. Many of the mill villages were extremely primitive, with livestock roaming freely in the muddy streets without sidewalks. In the very early 20th century, kerosene lamps lit homes and open coal fireplaces provided heat in cold months at the cost of spewing black soot over the house (see pictures at 58 Park Square.)

Water was drawn from community wells and sewage systems often amounted to no more than a row of utdoor privies. These conditions began to change around 1910 as mills switched to electricity. On Chicken Hill, Asheville Cotton Mill built the Clubhouse as a community bathing center where men and women bathed on alternating days (see Clubhouse.)

The families of workers who populated the mill villages tended towards restlessness and moved from village to village frequently. Due to their poverty, and the resulting poor diet and disease, millworkers experienced a life that relied on sharing and mutuality. From the formation of a region-wide workers' community emerged commercialized culture, especially radio and country music.

back to

top

Workplace Hazards

When southern farmers left the land to work in cotton mills they called it “public work.” Everyone worked. Men, women, children and elderly people all had a place in the mill. Social interaction was limited, if not ompletely prohibited, in the factory and terrifying hazards were rampant.

In the card room copious amounts of dust in the air caused irritation of the breathing passages which led to byssinosis. It was referred to as “Monday morning sickness” because after the lungs had time to clear over the weekend, the cough would set in again on Monday morning.

Conditions were even worse in the weave room. The constant mist descending from sprayers on the ceiling caused not only slippery floors near dangerous equipment, but created a perfect environment to give the workers tuberculosis. Unfortunately, many doctors did not recognize the symptoms as the result of the work environment.

The spinning room was incredibly hot all the time. Workers were not allowed to prop open the windows and the machine motors could easily burn the arms or legs of an unwary worker who bumped into them. There was very little medical help available to mill worker, and certainly no insurance or worker’s compensation. If you got hurt and could not work, you stayed at home without pay.

back to

top

Children and Mill Village Schools

The mill controlled nearly every aspect of life including offering land and funding for churches and maintaining close relations with the pastor, and providing a schoolhouse and teacher for children too young to be workers.

Between 1880 and 1910 manufacturers reported that about one-fourth of their work force was under the age of 16, with many full time employees as young as 12 or 14, and many child laborers unreported. By 1920 only around 3 percent of the children in these villages went to high school; most went to work instead, so the factory force was largely self-reproducing. Children were paid much less than adults and their wages were given directly to the parents.

back to

top

The Company Store and Welfare Work

To curb the migrant nature of the mill village families and to secure a loyal work force, many southern mill owners began to operate company stores. The idea was to extend the pay period until the workers were sure to run out of money then issue credit which could be used only at the company store. This ensured indebtedness and kept the mill workers in a plight similar to that of sharecroppers. And, of course, the mill owner could recover a large part of the wages he paid out by forcing his employees to buy goods from the company store.

However, by 1920 company stores started to decline due to growing financial independence of the mill workers. Many manufacturers turned to other means of securing faithful workers, particularly “welfare work.” Following the examples of the National Civic Federation and major northern companies, mill owners instituted a new campaign to beautify villages and provide some social services for their employees. This welfare work included building community centers, landscaping factory grounds, funding YMCAs, and organizing recreational and educational activities. Mill owners hoped that baseball teams and sewing groups would generate a sense of satisfaction among the workers.

Indeed, conditions did improve considerably for mill communities, but by no means was this work purely humanitarian; its main objective was to foster permanency of residence and regularity of work among the families of workers who turned the raw cotton into profits. As it turned out, welfare work fell short of owners’ expectations because the workers struggled to keep their own forms of expression and limit their dependence on the mill. By the time of the Great Depression after WWI, mill owners concluded that the payoff from welfare work did not justify the expense.

back to

top